Excerpted from articles by Carol W. Kimball The Day of New London, CT

Historian Eva L. Butler was a remarkable woman, and I was privileged to count her as my friend. She came to Groton in 1928 when her husband, S. B. Butler, was appointed superintendent of Eastern Point and Groton Heights Schools. At the time Connecticut was making plans to celebrate its Tercentenary and she was swept into a maze of preparations.

Involved in research to determine the town’s oldest houses she developed a notable map called “Old Homes and Home sites of Groton” showing those existing before 1800 and illustrated by her sister, Catherine Lutz. The map is in print in a map portfolio published in 1976 by the Mystic River Historical Society.

During the Tercentenary, Mrs. Butler interested a group in establishing the Fort Hill Indian Memorial Association, constructing a replica of an early settler’s home at the summit of Fort Hill where the Pequot sachem Sassacus had his fort in 1637. The place operated as a museum displaying Indian artifacts and colonial relics.

As a result of her interest in local Indians, Eva became involved in some of the first archaeological excavations at Fort Shantok, Poquetannock and Ledyard. She studied at the Universities of Pennsylvania and New Mexico, and worked at the Robert Abbe Museum on Mt. Desert in Maine.

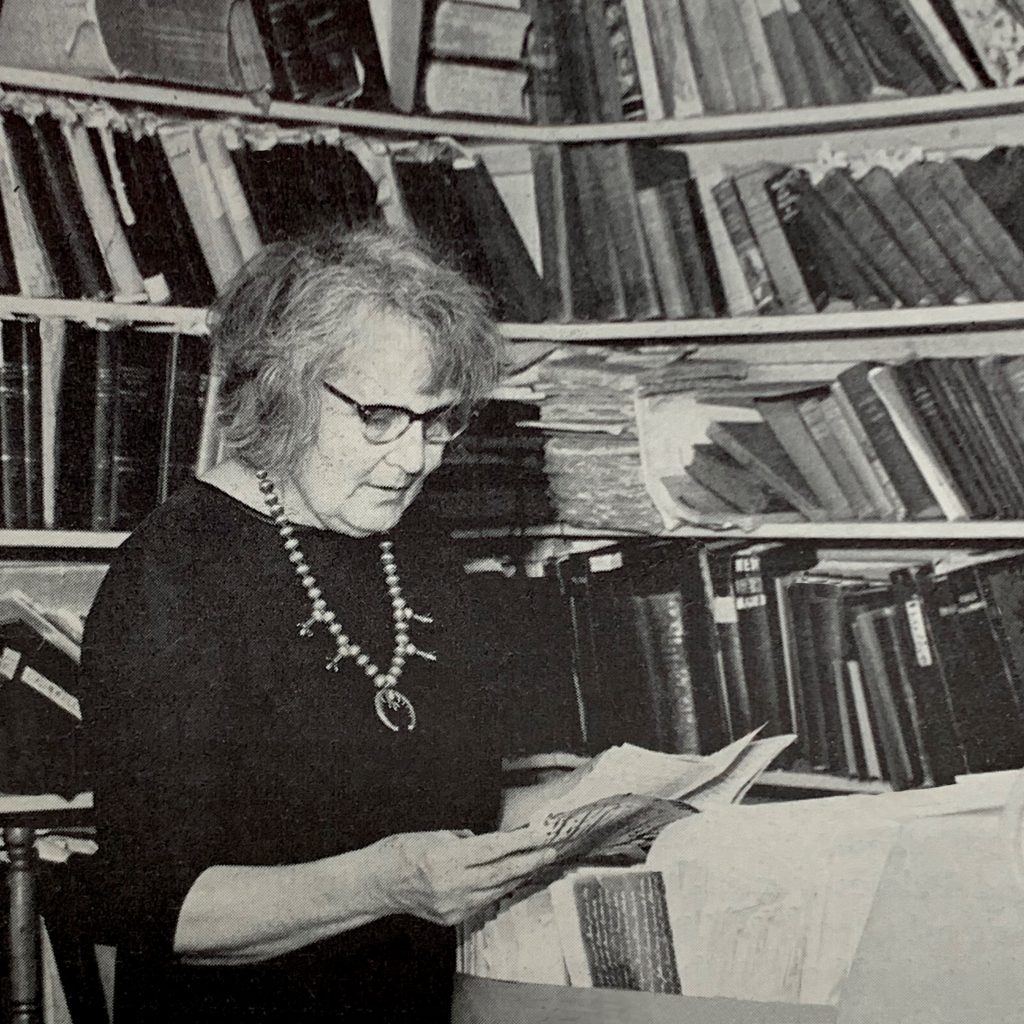

This tireless woman became acquainted with local Pequot and Mohegan Indians. Her photographs and notes are preserved at the Indian and Colonial Research Center in Old Mystic.

After the Butlers purchased the old James Woodbridge house on Gallup Hill in Ledyard, she taught extension courses there for Eastern Connecticut State University. Her classes were popular with teachers and included local history, nature study, archaeology, mythology and colonial literature. She and her students often prepared authentic colonial meals over her large fireplace.

Somehow, she found time to establish a Children’s Museum in New London, which evolved into the Thames Science Center. She later founded the Tomaquag Indian Museum in Ashaway, Rhode Island, where her large artifact collection was displayed.

Eva believed history should be written only from primary sources, and she early convinced me of that. She did not drive a car, but her many friends gladly took her to town halls and libraries for research.

Copious notes about her discoveries eventually filled more than two thousand loose-leaf notebooks, stacked in confusion on makeshift shelves lining the walls of her home. She was fond of typing her material on bright purple carbons for a copying machine, rolling off dozens of mimeograph duplicates. Some of these she distributed to her students. Others were filed in appropriate notebooks. Fortunately this ardent historian required little sleep and could devote long hours to her work.

She prepared concise summaries of all entries in the early volumes of New London and Groton Town Hall for their first volume.

Collections in the State Library at Hartford from the file on private controversies to probate records were investigated and were grist to her mill. She was fascinated with the Winthrop papers, a collection of letters written through the years by and to John Winthrop and his family. She found them at the Massachusetts Historical Society and carefully transcribed all that were pertinent to this area.

Friends constantly begged her to publish her work, but she would reply that she had not yet learned all there was to know about her subject. She had a horror of perpetuating errors in print as has been done in the past by careless historians. Besides, she was probably too busy answering requests from information from others who were writing books. She was always ready to help friends and strangers alike.

Sad to say, she published little in finished form except for a few articles and a children’s story “Two little Navajo’s dip their sheep”. She is listed in the Library of Congress for “Uses of birch-bark in the Northeast” (1957) by Eva L. Butler and Wendell S. Hadlock. (E98.I5 B88) and “Along the shore,” 1930 (QH1 .B84). Besides these few publications, she issued mimeographed titles herself from time to time. This was a great loss to our knowledge of local history for now we have only her working notes and unfinished writings which, without her own vast knowledge, are difficult to interpret.

Hospitalized with a heart attack in April 1965, she began to worry about the disposition of this valuable source material. A group led by Harry W. Nelson; poet, artist and retired teacher from Fitch High School in Groton; and Eva’s special friend Mary Virginia Goodman formed the Indian and Colonial Research Center, Inc. From the town of Stonington they obtained the unused 1856 brick building in Old Mystic that once housed the Mystic Bank. They have been restoring it ever since. The original officers of the corporation included Philip Perkins, treasurer; Jessie W. Kohl, corresponding secretary; and Carol W. Kimball, recording secretary.

With a $2000 grant from the Bodenwein Public Benevolent Foundation and muscle power and good hard work on the part of Harry Nelson and architect Sanford Meech, shelving was installed, furniture painted and a heating system provided. From the old farmhouse in Ledyard, thousands of notebooks and manuscripts and hundreds of printed volumes were moved to their new home.

By the summer of 1966, the center was in full swing, staffed entirely by volunteers, ready to help anyone interested in Indian lore, local history, genealogy, historic photographs and other phases of Americana. The organization, which now numbers over two hundred members, has preserved these papers making the Eva Butler library available for public research.

Eva Butler died in 1969 but her work goes on, a vital community resource supported not only by its members but by grants from local foundations and service clubs. A collection of Indian artifacts has been added to the original library, and an educational program has been developed by the staff for the benefit of area schools.

Some additional memories

by Jacqueline Butler Zeppieri (granddaughter)

My grandmother, Eva Lutz Butler, definitely preferred to be out-of-doors, having a lifelong interest in nature, botany, birds – every kind of natural science. She took us grandchildren on scores of woodland walks that she had enjoyed so much herself, pointing out plants and their names, and bringing home gallon jugs of pollywogs so we could watch them turn into baby frogs. Being a naturalist, of course she made sure they all went back to their pond as soon as the science lesson was completed. She recorded bird songs and helped us learn to identify the many birds in the Ledyard woods and fields surrounding her home. She let us help with Colonial candle-making using bayberries. We children were given pieces of string which we dipped into coffee cans of the wax mixture she had made. We were instructed to dip our string and then march once around the large downstairs of her home (built in 1732) through four rooms circling a massive fireplace, singing “Dip, Dip, Let it Cool,” before dipping again and repeating the process.

I know she loved to ice skate as a young girl. It’s mentioned many times in her letters. Being the oldest child and a daughter, though, I don’t think she was what we think of as a tomboy. She knew how to crochet and knit and I remember her putting a “Lazy-Daisy” embroidery stitch on a little blanket while she baby-sat with us, about 1950.

She was unconcerned about “lead-time” when she wanted to do something. Sometime in the ’60’s she published a general invitation to the public and members of the Tomaquag Indian Museum to come for a Blueberry Festival–a meal with blueberry pie for dessert. Around the same time that most of the guests were arriving she sent my sister and me out to pick blueberries to make the pies! I have blanked out how we did it, but knowing my grandmother I have no doubt that eventually there were indeed blueberries pies for the festival. She was definitely a positive thinker.

Gifts from the Butler family honor their father

On August 12, 2014, Jackie Butler Bieber, Sewall Butler Jr. and David Butler presented I C R C with a plaque, a portrait, a notebook about Sewall and a $1000 check in memory of their father Sewall Tolbert Butler who passed away earlier this year. Sewall, the son of I C R C ‘s founder Eva Butler, was a native of Mystic, a graduate of Fitch High School, and a World War II veteran. He was a lifetime member of I C R C and was named honorary director in 2001

From left to right: David Butler, Kinberly Hatcher-White, Allen Polhemus

From left to right: David Butler, Kinberly Hatcher-White, Allen Polhemus

Robert Mohr, Joan Cohn, Jackie Butler Bieber, and Sewall Butler, Jr.

The third-generation Butlers reminisced about the many visits they and their father paid to Grandmother, Eva, and how they would attend harvest festivals, dances, and participate in archeological digs. Sewall, Jr., recalled, ” It was a fun time. It was a big part of our life being here from childhood all the way until we went to college “

From left to right: Erwin ‘Red’ Bieber, Joan Cohn, and Jackie Butler Bieber