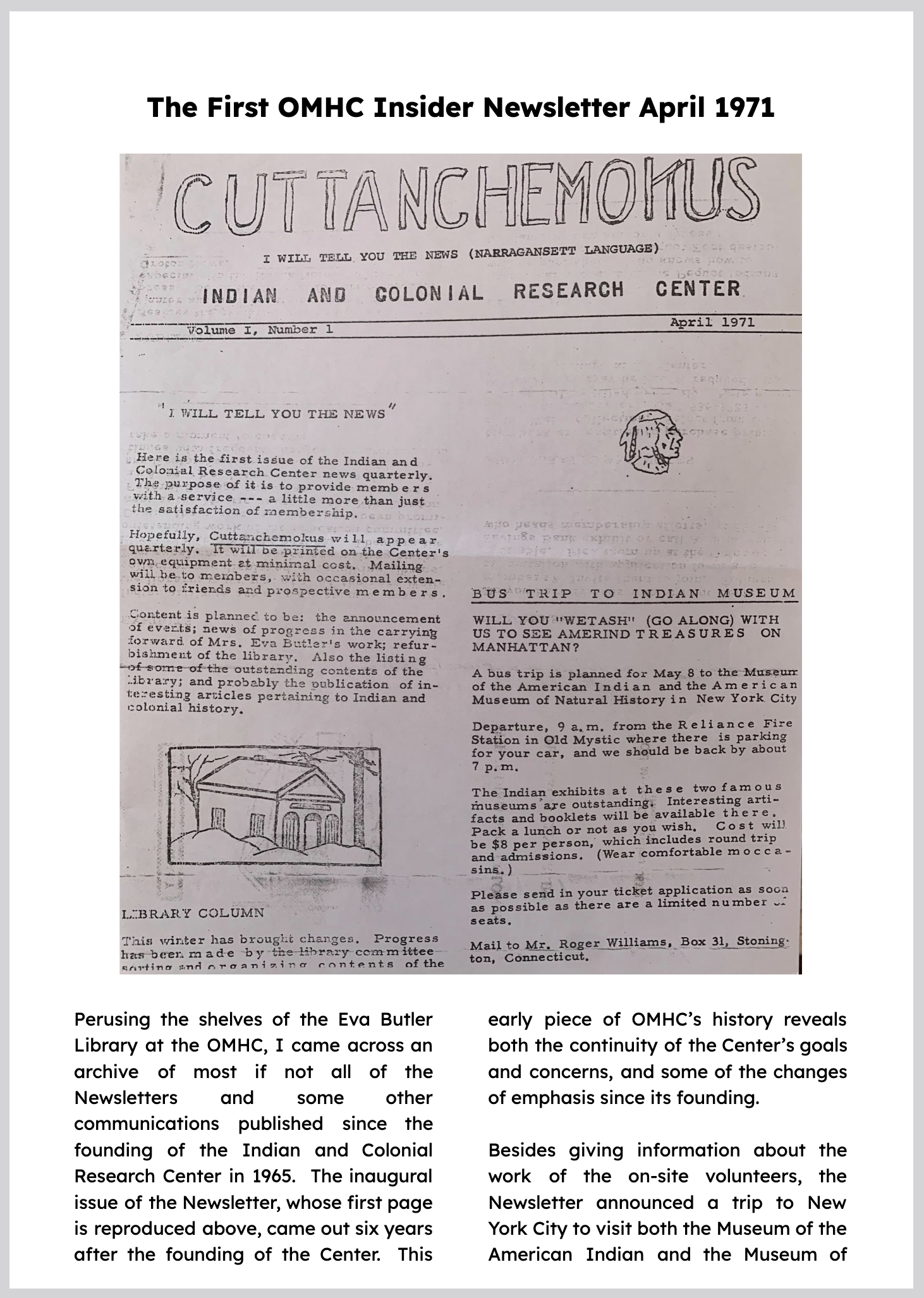

|

|

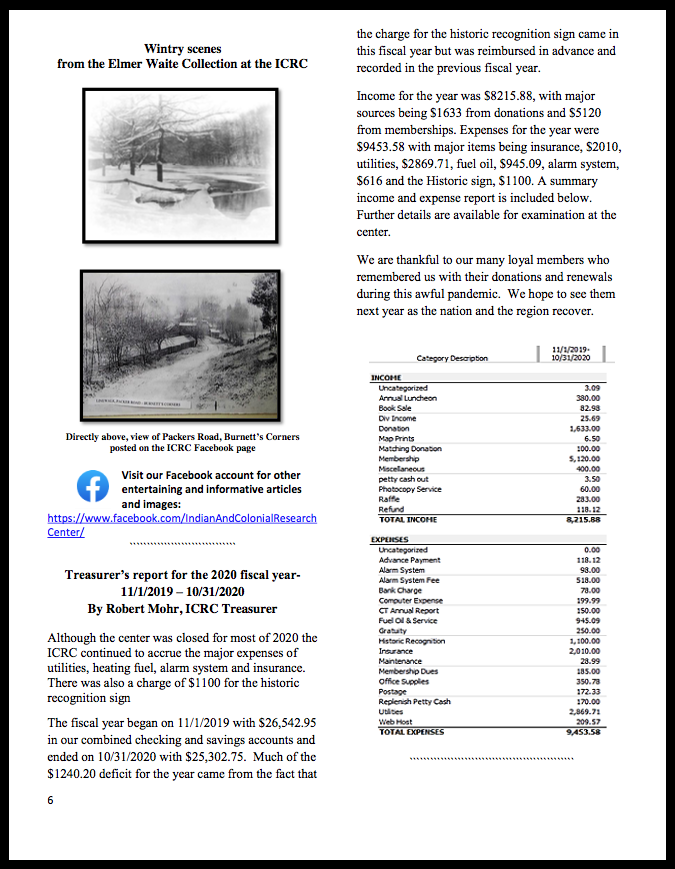

Happy Birthday America July 4th A Few Fun Facts

July 4, 1777 was heralded in Bristol, Rhode Island with a 13-gun salute in the morning and again in the evening. The celebration became an unbroken annual tradition in 1785 and 230 years later is the oldest July 4th party in the United States !

-

- Philadelphia celebrated the Declaration of Independence’s first anniversary with food, drink, prayers, parades, and fireworks. Ships in the harbor were festooned with red, white, and blue bunting.

-

- On July 4, 1778, from his headquarters in New Jersey George Washington ordered a double ration of rum for his soldiers.

-

- While Washington’s men were enjoying an extra libation, Benjamin Franklin and John Adams, ambassadors to France, were hosting a dinner for fellow Americans in Paris.

-

- In the 19th Century New England towns sometimes competed with each other for building the largest and most impressive bonfires to mark the occasion. Hogsheads and barrels were thrown into heaps sometimes 40 tiers high then lit at night for splendid effect.

- In 1938 Independence Day became an official paid national holiday.

|

|

Old Mystic Community Picnic – Summer fun !

Come join the fun on Saturday July 18th, from 11 am – 2 pm , when the Old Mystic Fire Dept., the Old Mystic Community Assoc., the Old Mystic Baptist Church, the Old Mystic United Methodist Church, and the I C R C sponsor a community picnic at the Old Mystic Playground and Ball Field on Haley’s Way in Old Mystic. Hamburgers, hotdogs, and beverage will be provided. You just need to bring a salad or dessert to share.

|

|

Thank you, Mystic Women’s Club!!

The I C R C is very grateful for the generosity of the Mystic Women’s Club for their recent donation of $1,036! The money was raised through their Military Whist event, coordinated by Ruth Williams, one of I C R C ‘s loyal members. This gift will be very helpful as we develop community outreach and educational programs. Many, many thanks!

|

|

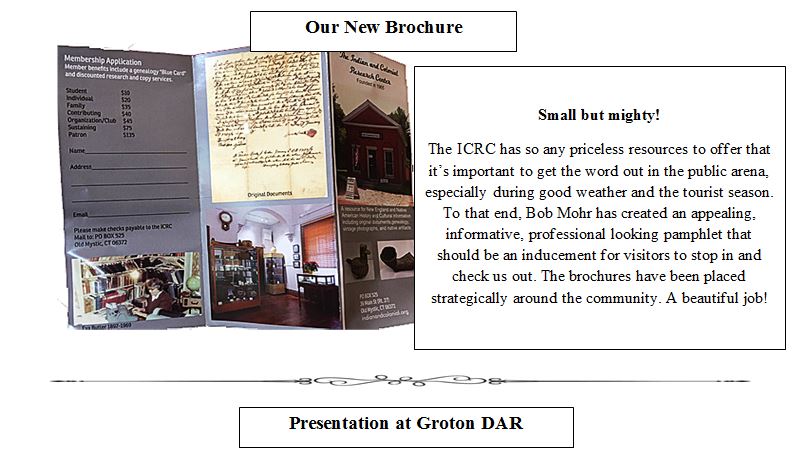

Don’t Miss it – Mark Your Calendars for

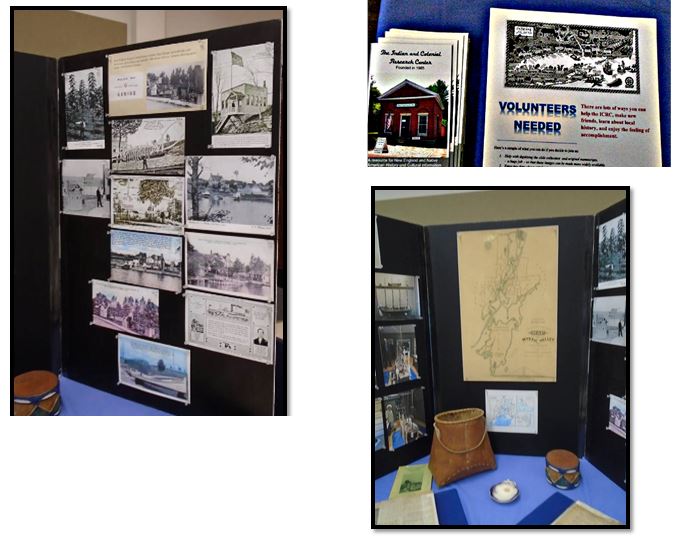

The I C R C Photograph Exhibit

At the Mystic & Noank Library

Month of October

As part of sharing the celebration of our 50th Anniversary with the community, the I C R C will mount an exhibit of some of our extensive photograph collection at the Mystic & Noank Library. The pictures will be on display in the Ames Room from Monday, October 5, through the end of the month. The library is located at 40 Library Street in Mystic. A complimentary wine and cheese reception will be held October 5th from 7 to 8 PM. Please plan to join us!

|

|

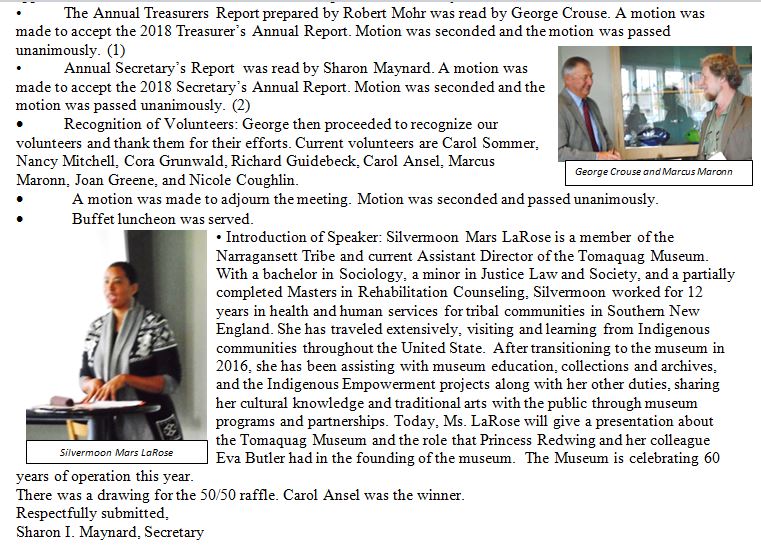

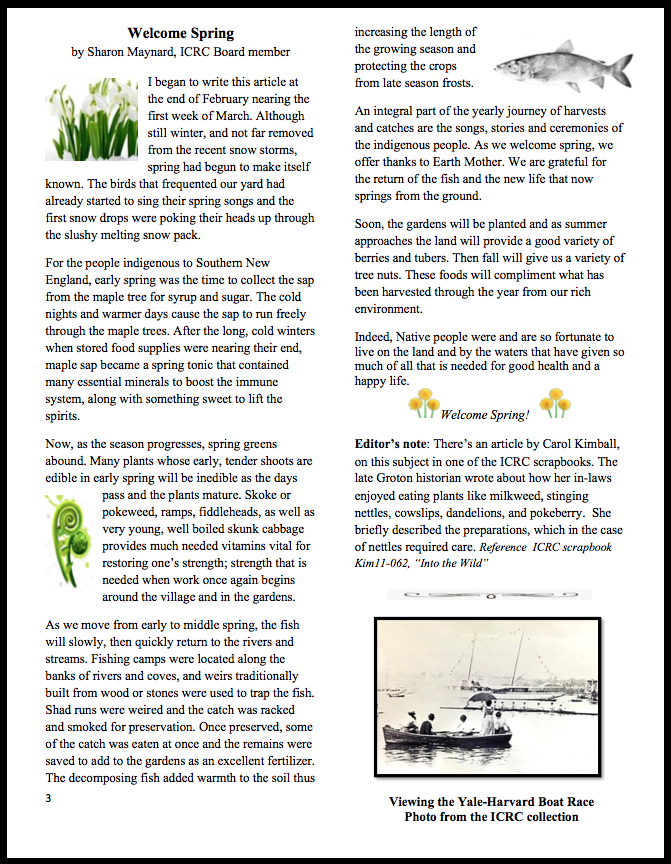

Old Mystic Teenager Goes to War

“Whenever I am called upon to go into the field of battle I shall go…”

William Fellows. A book review by Carol Sommer

2015 marks the 150th anniversary of the conclusion of the Civil War. The experiencer of a local teenager participating in America’s epic conflict are captured in a collection of letters held by the I C R C and transcribed by Gloria J. Fowler. Published as a book in 2009 (available for purchase at I C R C ), the letters that William Fellows wrote home to his mother and sister provide insight into the conflicting emotions of homesickness and excitement that the young soldier, like so many other enlisted men, must have felt.

William was stationed first in Norwich, then New York, and finally at New Orleans in preparation for the assault on Port Hudson – a battle with a worse casually rate percentage-wise than Iwo Jima or the Normandy Invasion.

After the Confederates surrendered Port Hudson, Abraham Lincoln exulted that now the Union had the strategic advantage of full control of the Mississippi River.

William’s letters outline daily life and military duties, the frustrations of sporadic mail deliveries, and the problem of delayed pay.

He may have been trying to put the best face he could on his experiences because the letters are generally cheerful – except one angry outburst about not getting enough correspondence from home.

For readers who grew up in or near Old Mystic the book is engaging because William mentions many local families, still familiar today, whose welfare and activities he wanted to stay in touch with.

William also described for his mother and sister the areas that he saw and how they differed from Connecticut. Although he was always clear that he couldn’t wait to get home again, he felt the excitement of what seemed like traveling through a foreign country. He thought Key West looked lovely from the troop transport vessel. He admired Louisiana’s mild climate and unusual flora, but the fauna – mosquitoes – not so much.

The story ends with William’s death, probably from typhoid, just as he was scheduled to go home. His letters give the reader a sense of William’s strength of character and his sweet nature, and make his loss all the more tragic – for him, his family, his community, and us. It brings home how much we owe to so many like this brave young man.

|

|

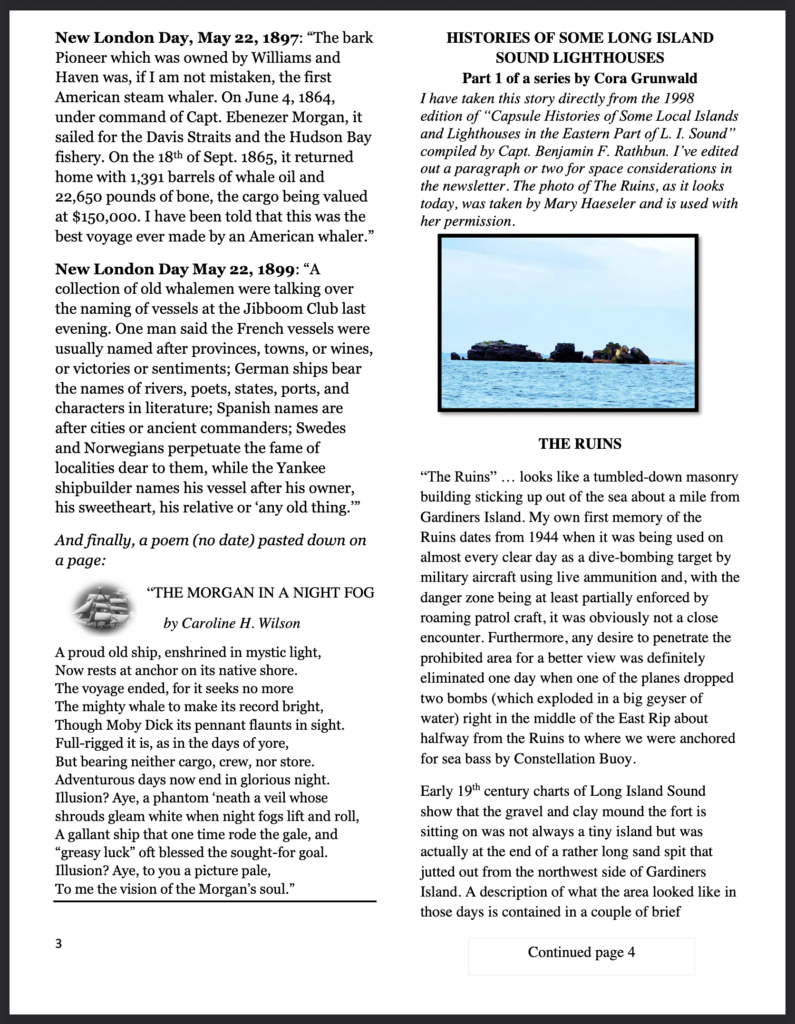

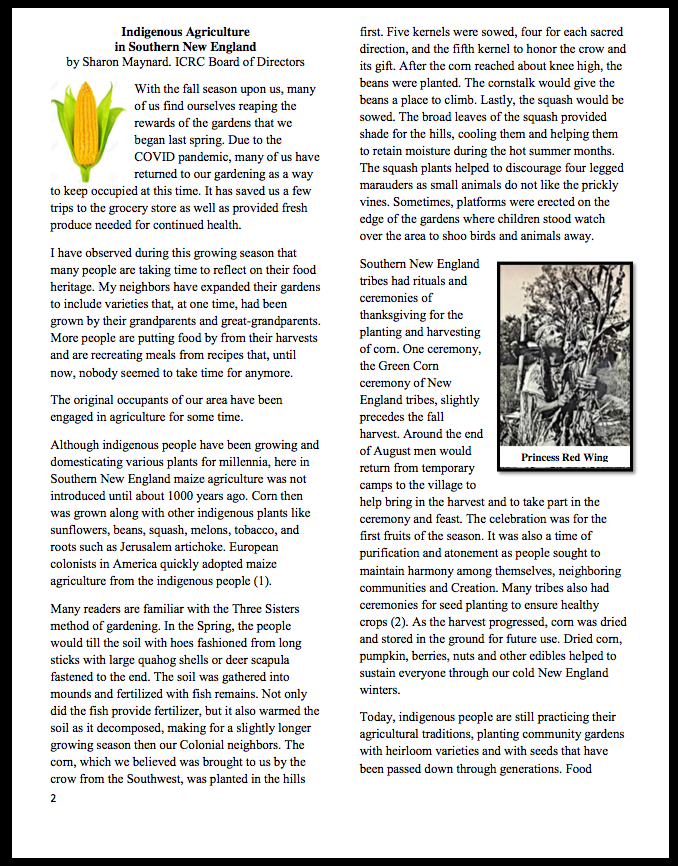

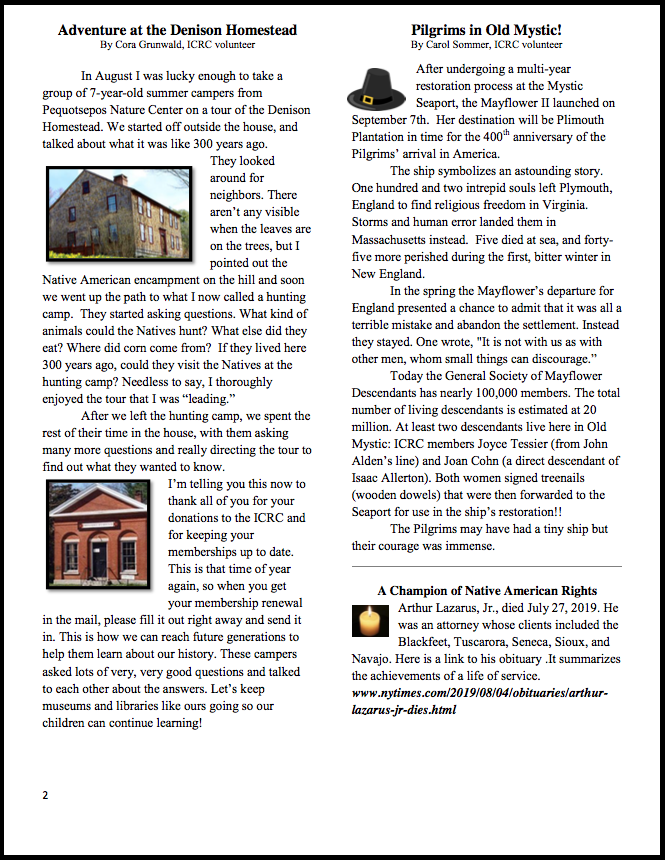

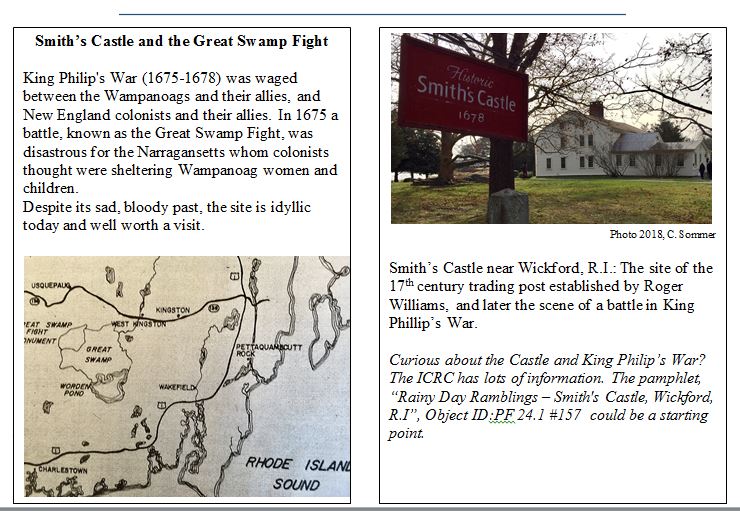

A Place of Indian Curios and Relics

By Paul Grant-Costa

In 1978, the remains of an obscure and abandoned Indian museum were removed from the top of Fort Hill in Groton. The New London Day referred to it as a “Forgotten Indian Memorial.” Groton historian Carol Kimball summed it up pretty well by saying “There’s been an awful lot of puzzlement about it. It’s just sitting there and everybody sort of wonders what it was.” Today, Kimball’s quip is even more relevant, as passersby traveling up Fort Hill on Route 1 see no trace of where the structure once stood. But from 1935 until 1941, the building and its contents introduced many New London County residents and visitors to the area to the subject of New England Indians, Native culture, lore, and archaeology.

Historical Sketches of the Town of Groton

for Connecticut’s 300th anniversary

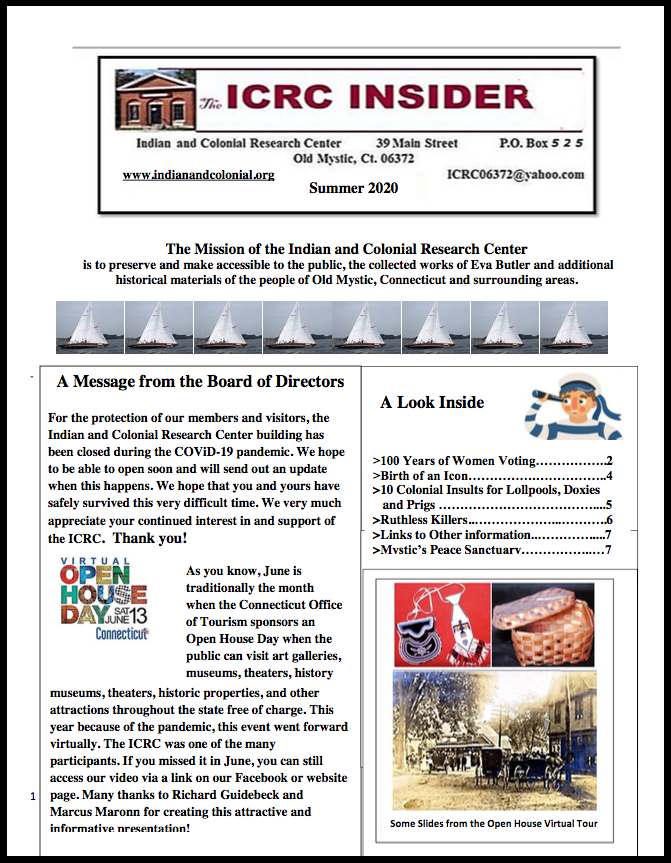

When the Town of Groton prepared for the celebration of Connecticut’s 300th anniversary in 1935, Sylvester B. Butler was the chair of its central planning committee, and his wife, Eva Luz Butler, was chair of its Indian Memorials program. That enterprise was originally tasked with getting Groton’s Boy Scout troops to construct a log cabin that would house a collection of “Indian curios and relics.” Others on the planning committee included Norman S. Bosworth, J. Halstead Brown, Raymond C. Bugbee, Lloyd Gray, Clarence Hall, Ernest Land, Roscoe Merritt, Mrs. Roswell P. Sawyer, W.S. Thomas, Charles Stribl, Herbert Coit, and Helen Glidden.

Frank L. Merritt of Groton gave land on Fort Hill for the Indian memorial museum to the town. Directly opposite the Chasanba Lodge on Route 1, the property was part of the Merritt family farm and had a significant Indian legacy. It was the site of the Pequot sachem Sassacus’ fortified village during the Pequot War and served as a settlement for Robin Cassacinamon’s band of post-war Pequots in 1647, known as Robin’s fort hill.

With only a few months until the anniversary celebrations, the committee worked hard to meet the opening deadline. Meeting at the nearby Chasanba Lodge, they refined the plans and developed a larger design for the museum site. It would include an Indian longhouse, a wigwam, and a palisade to surround it, representing a recreated “village” of a sort. While the initial concept proposed constructing a log cabin, not enough logs had been donated and none could be found in the short time needed to build the structure without costly expenditures. As an alternative, the planning committee settled on a house similar to a reconstruction of the first trading post in America recently erected by the Bourne Massachusetts Historical Society. For the supplies, they secured materials from two 18th Century houses, the Burrows place north of Center Groton, which was donated by Charles E. White and the Stoddard Homestead from Ledyard, a gift of Judge Billings Crandall. Committee workers salvaged hand hewn beams, pine and butternut paneling, hand-ribbed shingles, hand wrought iron latches and hinges. Also recovered were stones to construct a colonial fireplace and a beehive oven.

Because these structural changes in the trading post required more experienced builders than a troop of young boys, the town, as owner of the property, offered the services of a team of Federal Emergency Relief Administration (F E R A) workers. In July of 1935, ten men and one foreman began constructing the one story trading post. Groton’s Scout Troop 13 worked with the Indian memorial committee in erecting an Indian village.

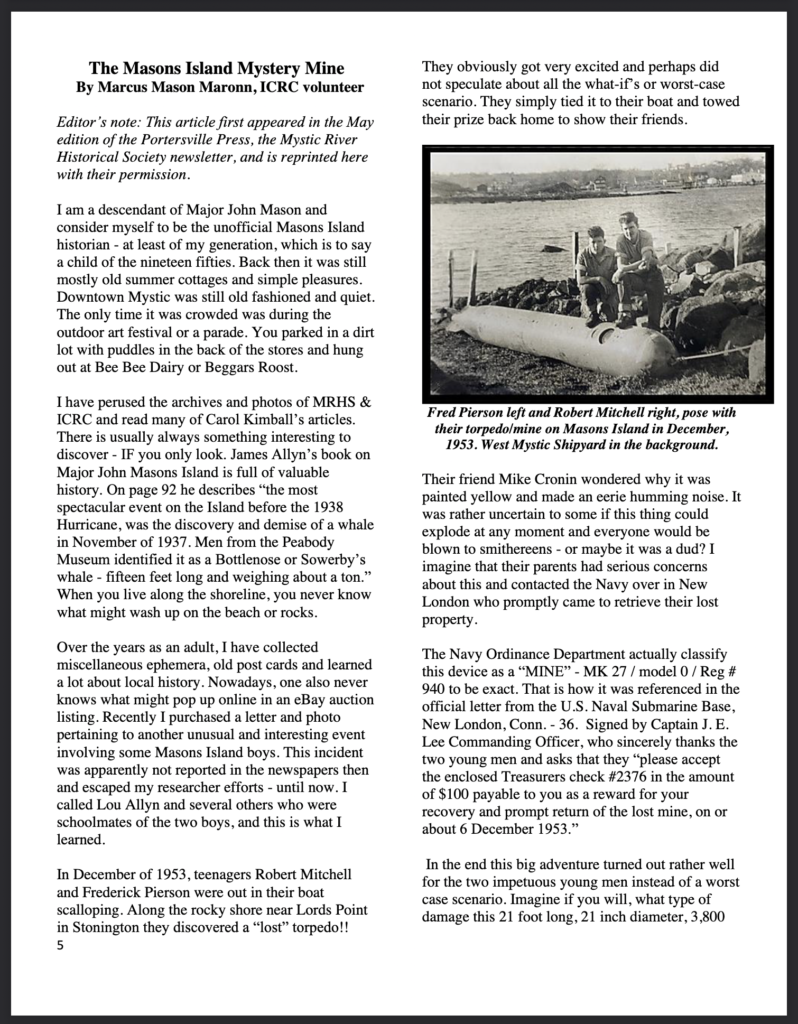

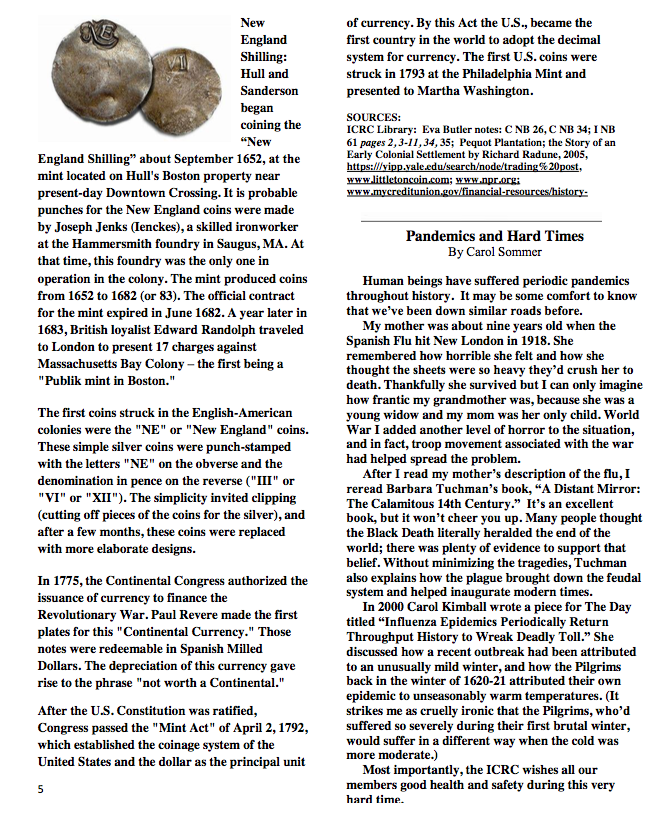

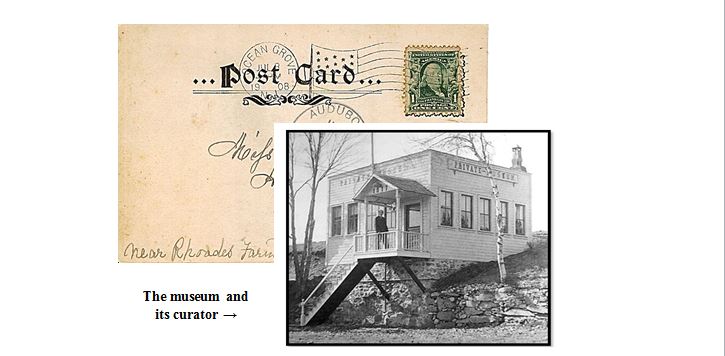

Photograph of Indian Memorial trading post (1935)

When the one room house was completed, local people donated or loaned the committee artifacts for display. A 1935 New London Day article mentions an extensive collection of archaeological artifacts–wampum, mortars and pestles, paint pots, medicine pipes, banner stones, and hundreds of arrow and spear points and tomahawk heads–and of ash and oak Indian baskets, the rarest coming from the nearby homestead of the Avery family. Other Indian goods included a 150 year-old wooden ladle and a mortar said to go back to Uncas. Along the side of the fireplace, stood relics of all kinds–a low bench, cauldrons from old kitchens, a wood reel, a cobbler’s candlestick, old tools, bellows, a foot warmer, a flax hatcher, and a waffle iron with a long handle. On an old chest stood a candle mold, a chopping bowl, a bootjack, and a warped boot. Hanging from the fireplace were spoons and kitchen utensils. Outside the trading post, an effigy named John Dough, a “bedraggled little man,” stood dolefully in a pillory for his crime of habitual laziness.

The main building opened during the last week of August, when other tercentenary activities were scheduled on the Merritt family farm at Fort Hill. The Merritts cleared two acres of their fields and installed lights there for the production of an historical pageant entitled “The March of Time,” that would be held on Tuesday, August 26th as part of the “Old Home Week” program. With nearly 400 participants, the event drew a crowd of 3,000 spectators, who seemed to enjoy watching Groton’s interpretation of local history, from the opening Indian dance and reenactment of the Mystic fort fight to the last episode commemorating World War I.

Visitors at the Indian Memorial could experience colonial history personally by viewing and sometimes touching the items. Some people enjoyed photographing each other in the stocks. Others bought souvenirs and copies of interesting documents, maps, and illustrations about the local Indians. In the opening month, the museum registered close to 500 visitors, many coming from around the country. Some were from as far away as Holland, Norway, and Canada.

By the end of September the idea was to maintain the Indian memorial permanently as a facility for the study of Indian lore to be managed by a group called the Fort Hill Indian Historical Association with the cooperation of the girls and boys organizations of the town. On one September night, about twenty of the fifty-one people who were interested in forming such an association met at the Groton Town Hall at Poquonnock and commissioned a committee to draft a charter and outline the duties of the chairmen and officers. Most of the members of the group were from the Groton Tercentenary Memorial committee, but others had joined in as well.

The objective of the Association or Historical Society, as they were also known, was to pro mote the study of American Indians, particularly those who lived in the New London area; to encourage scientific research in historic and archaeological fields; to conserve important archaeological sites and historic spots and preserve implements and sundry Indian artifacts; to make available to the public through exhibits the results of the endeavors, and to care for the Fort Hill Museum and the Indian burying place at Buddington Road at Poquonnock. Dues were set at one dollar a year, which entitled members to a season ticket to the museum and occasional bulletins, as well as membership in the society.

The following month a slate of officers had been selected. Elected were Eva Butler as president, Charles E. White as 1st vice president, Billings F. S. Crandall as 2nd vice president, D. Palmer Brown as 3rd vice president, and Betty Wheeler as secretary treasurer. Board of Directors was William Thomas, Raymond Bugbee, and Frank Kohl. Carl C. Cutter was the editor. Frank Kohl served as chairman of fieldwork and leader of archaeological expeditions. Raymond Bugbee and Roscoe Merritt were responsible for weatherproofing the museum building and paneling the interior. Mrs. Russell P. Sawyer was appointed chair of the program committee; William Thomas, the chair of the grounds committee; Norman Bosworth, publicity; and Ernest Lamb, exhibits. Based on the success of the museum, the society planned to open in the summer months each year and offer programs and public lectures during other seasons.

Letters were sent out to persons who were thought to be interested in Indian history and lore and in collecting and preserving Indian artifacts. “It is hoped,” Eva Butler said, “the museum will be a growing thing that will be worthy of the historic site on which it is located, a place where interested persons can come to learn of the manners and customs of the people who lived there long ago.”

The society held annual meetings at the Chasanba Lodge, accompanied by a supper and speaker. In 1936, after spending a large part of the summer in New Mexico, Eva Butler spoke about prehistoric and modern Indians in the Southwest. At that meeting, the Association sold maps of Groton with sketches of old houses, the proceedings of which were being collected to pay the expenses of a curator for the museum. That same year, Alice Morgan was hired for that position.

In 1937, the society included several archaeological expeditions, planned by Frank Kohl of Noank. The following year, the program and exhibit committee met to arrange new exhibits. Member volunteers took turns to keep the museum open, with a goal of weekend afternoons throughout the summer until Labor Day.

In December of 1938, the road from West Mystic to Noank was being improved as part of a Public Works Administration project. Road lanes were being widened, curves straightened, and new portions of the road laid out. This caused much concern for the society, for the road improvements, they believed, would be going through or be very close to an Indian camp site and burial ground they had found documented in several old deeds. To prevent destruction of the site and the artifacts, they offered a solution. Eva Butler and others were successful in persuading local and state authorities for permission to run an archaeological salvage excavation of the area to run ahead of the road crew, digging several five-foot square trenches. A representative of the society along with a surveyor from the state highway department would monitor the progress of the advancing construction. Any relics found, the society said, would be placed in the Fort Hill museum. Any bones uncovered would be reburied locally.

Harvey Stewart of Mystic, who claimed to be an Indian, and the head of the American Indian Foundation, criticized their efforts. Stewart made several public protests against excavation, arguing that Indian burial grounds should be held with the same respect as a white man’s cemetery and the road development be rerouted. In the alternative, he proposed that a representative of the State Park Commission, who had legal authority over Connecticut’s Indian tribes, be present as a monitor at the construction, and that any artifacts found be sent to Harford, any bones be sent to the Fort Shantock burial ground in Montville. However, after meeting with one of the society’s officers, most likely Eva Butler, Stewart withdrew his objections.

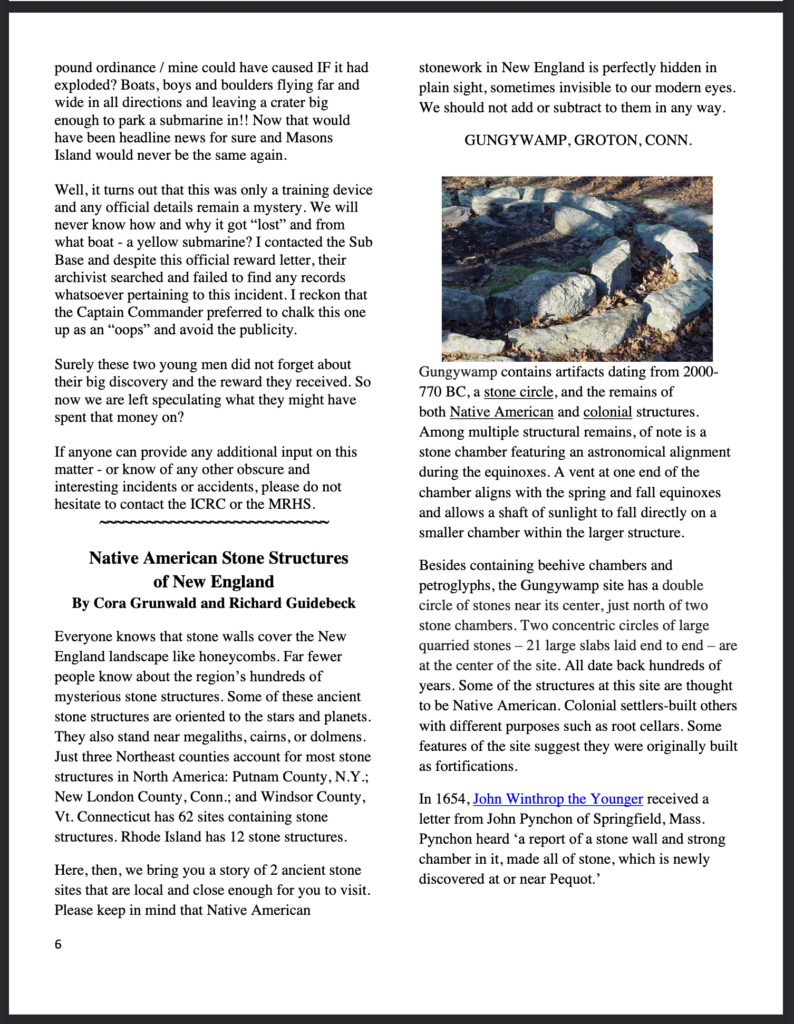

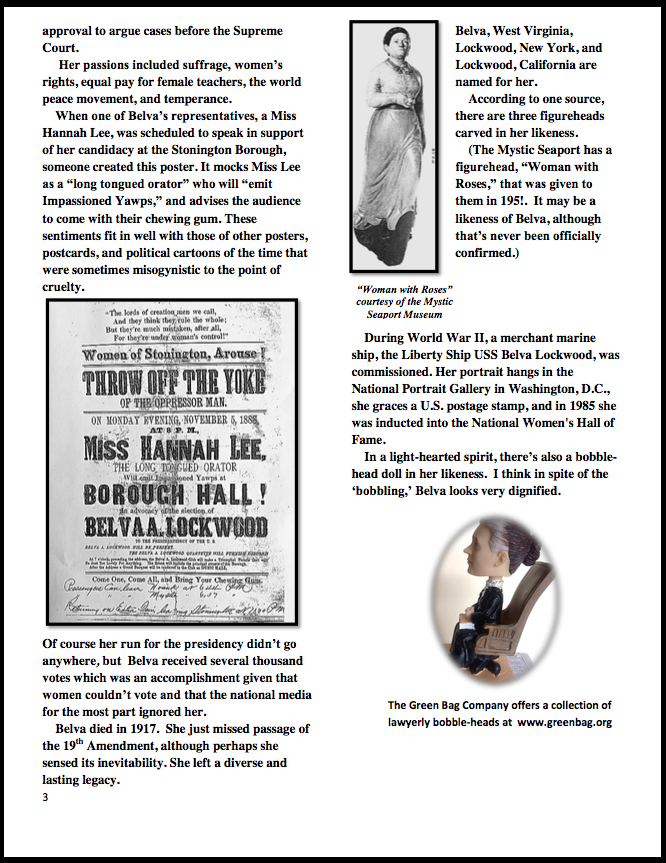

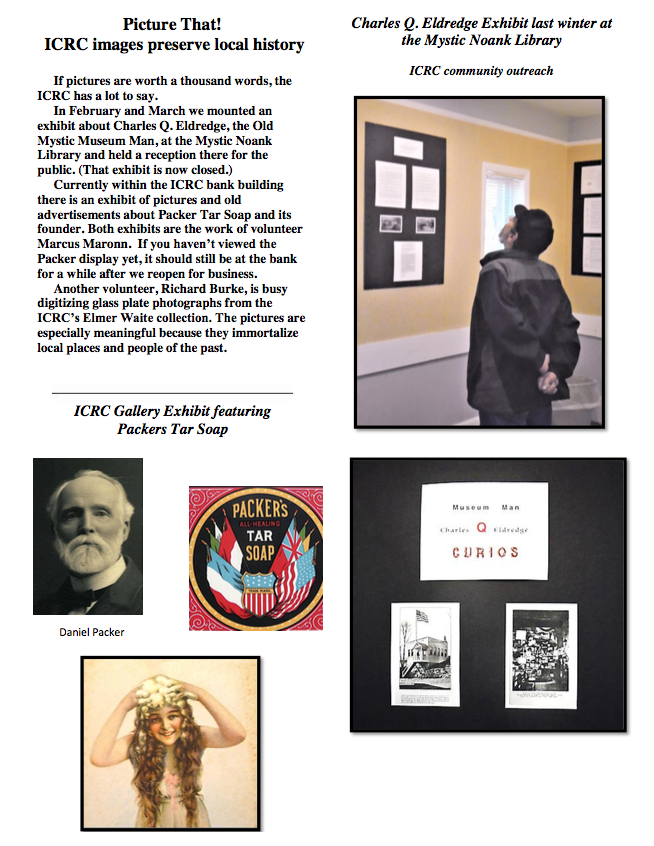

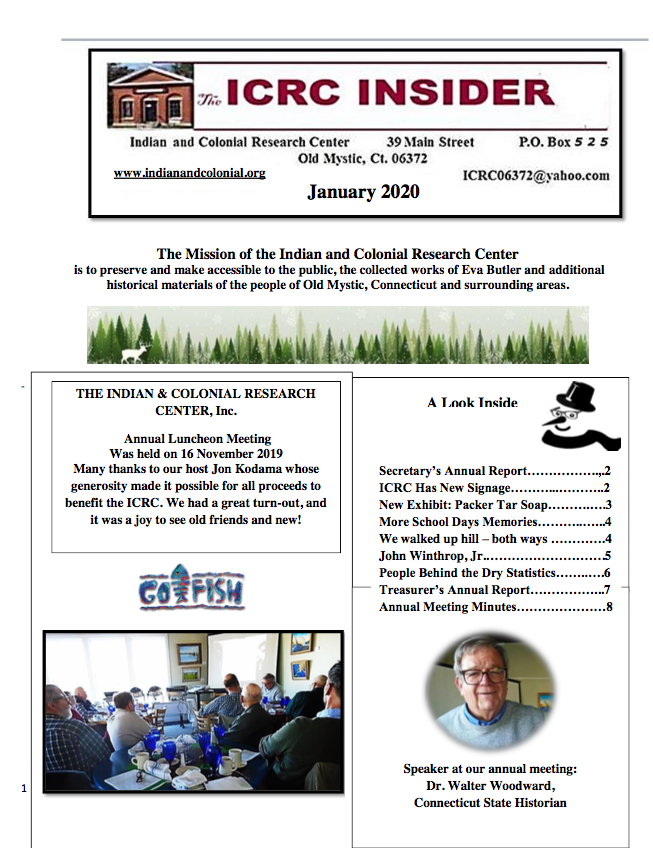

Eastern Pequot Tribal representatives at West Noank road construction site

Support for Butler’s plan came from members of the Eastern Pequot tribe at Lantern Hill who approached the society after learning about the situation. Tribal representative, Atwood Williams, Jr. (Leaping Deer), after visiting the site with his mother, wife, and son, offered to assist in the excavations. By the end of February, however, wintery weather slowed the society’s progress. Only one five-foot trench had been dug, and no burial ground discovered. But the society maintained its vigilance and dedication to protecting Indian sites in harm’s way. In the spring, Frank Kohl proposed a dig opposite the schoolhouse in West Mystic where there was an early Indian village in the way of the path of other Noank and West Mystic road improvements.

For several years, finances for the Indian Memorial House, as it was called by the townspeople, were affected by the recession of 1937-1938, and outside funding for its programs were slowly drying up. The facility was opened on Sundays and Wednesdays from 2 to 7, except for the winter, but began to have problems in staffing, especially by 1941 with World War II starting.

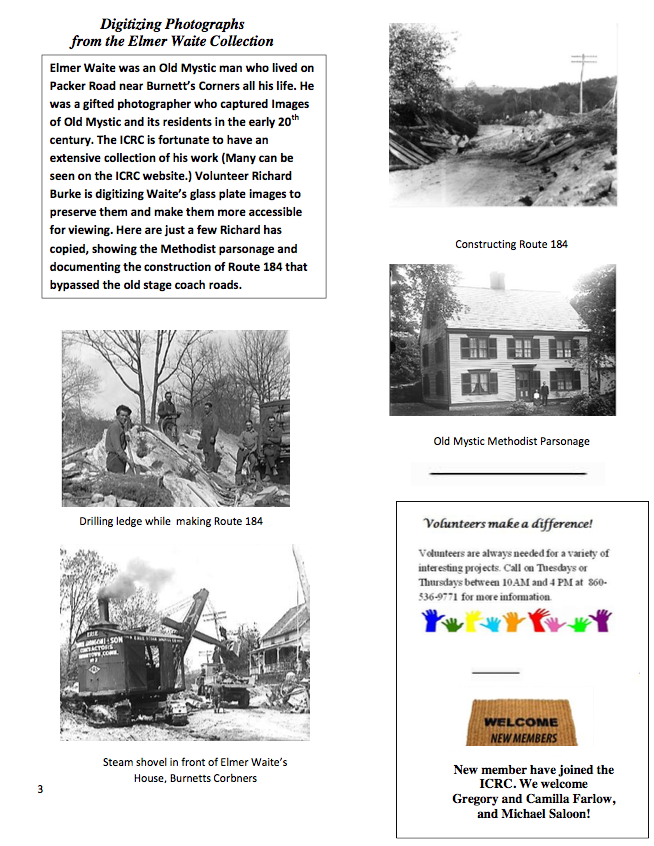

The abandoned Indian museum as it looked in 1964

The Fort Hill museum ended with no fanfare. Artifacts were returned to their owners, and the rest of the collection moved to the Butler residence on Gallup Hill Road in Ledyard. It is unclear when its doors were closed. It most likely came in 1941 when a request was made by Francis Merritt to have Groton quitclaim a right of way across the museum’s grounds. This may have been to provide access to a newly constructed residence on the parcel of land directly behind the museum, which would have made parking for the Indian Memorial House visitors a growing problem.

The closing of the museum may have also been time for Eva Butler to move on to new adventures. That same year she received her BA from the University of New Mexico. Soon thereafter, she was studying at the University of Pennsylvania for her Masters degree. In 1948, Butler became one of the founders of the New London County Children’s Museum in New London and served as its program director. In 1959, she founded the Tomaquag Indian Museum in Rhode Island with the assistance of Princess Red Wing of the Narragansetts. With a trading post, council rocks, wild animals and a museum display, Tomaquag represented what the Fort Hill Indian Monument could have become. In 1965, after Butler was slowed physically by a heart attack, she opened the Indian & Colonial Research Center to house her vast collection of papers, books, and manuscripts, leaving the Fort Hill museum as just a memory.

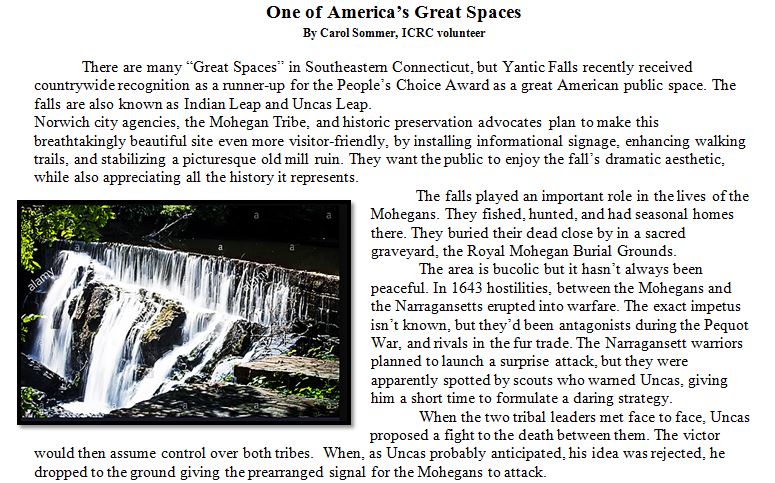

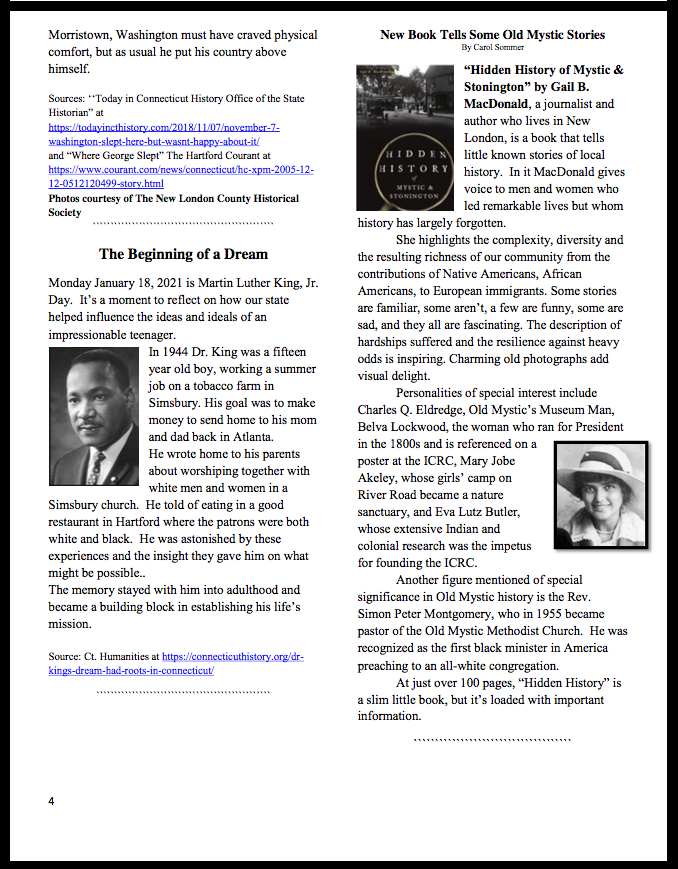

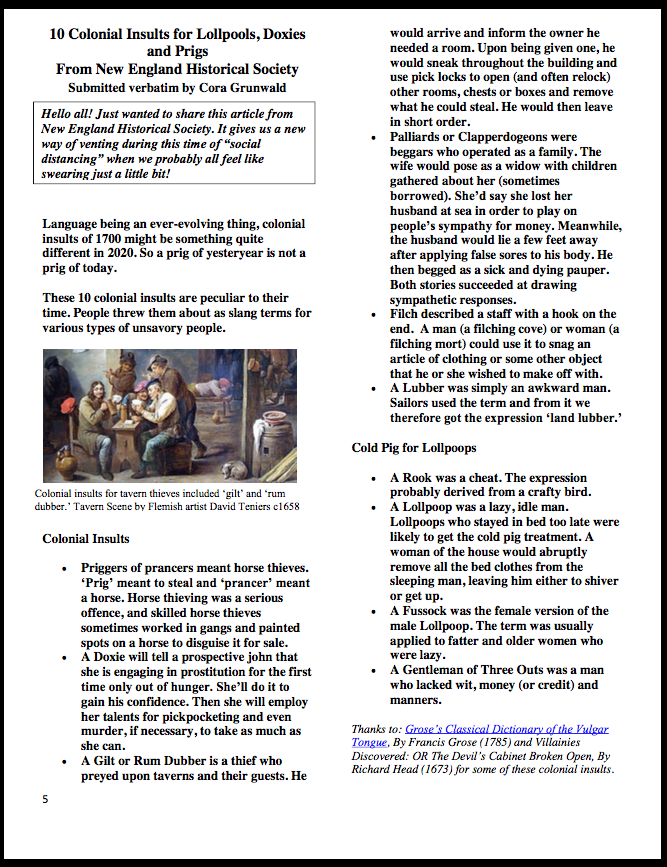

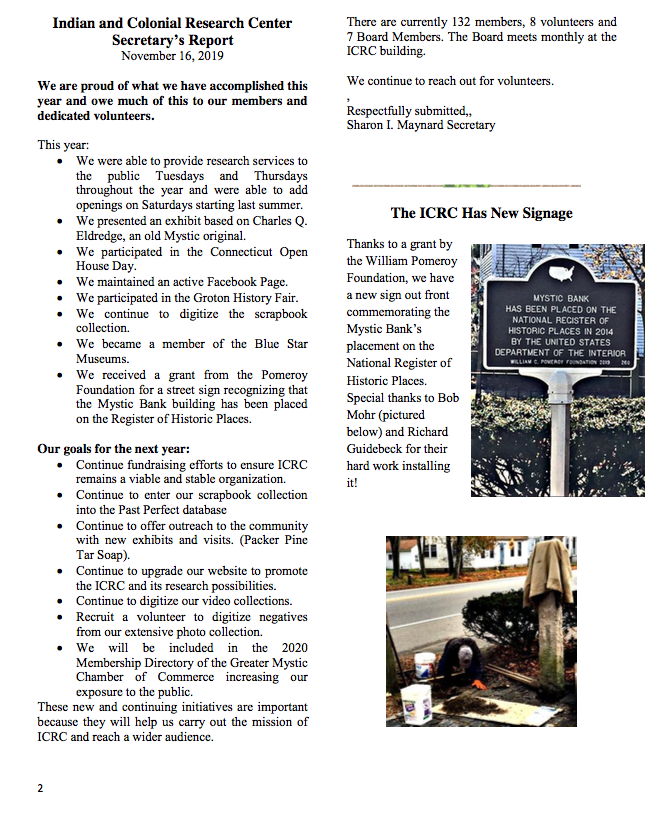

Indian Memorial House after storm damage in 1977 Indian Memorial House after storm damage in 1977

By the late 1970s, the abandoned old trading post on Fort Hill had fallen into disrepair and had an uncertain future. A local newspaper told of its decline. “The building has been deteriorating for years, unnoticed by passers-by for decades. It is a weather-beaten structure partly obscured by bushes and shrubs.” A windstorm in 1977 collapsed the roof and rear wall of the house. The Town of Groton weighed the options of repairing it or tearing it down.

After the storm, William Shea, a 14-year old Boy Scout from Mystic’s Troop 20, charging the town with neglect over the condition of the premises, requested permission to restore the building as part of earning his Eagle badge. But town’s Community Development Committee had other plans. In 1978, the town council accepted a proposal by Stephen Mack, a Rhode Island contractor who wanted to take down the dilapidated building and use the wood in the reconstruction of old houses. The town suggested he leave the chimney in place on which would be placed a memorial plaque to the Pequot Indians. Instead, Mack said that a chimney would be a poor memorial to the Indians and suggested a 25 foot oak tree with an Indian peering out into the distance and a boulder surrounded by stones and displaying a bronze plaque.

In June of 1979, Mack dismantled the trading post and restored a building near his house in Ashaway with the wood. But afterwards, there were concerns about whether the site was the proper place for a memorial. In 1979, the Groton’s Lion’s Club donated $300 for a plaque but a decade later, no marker had been placed at the Fort Hill site or any where else nearby.

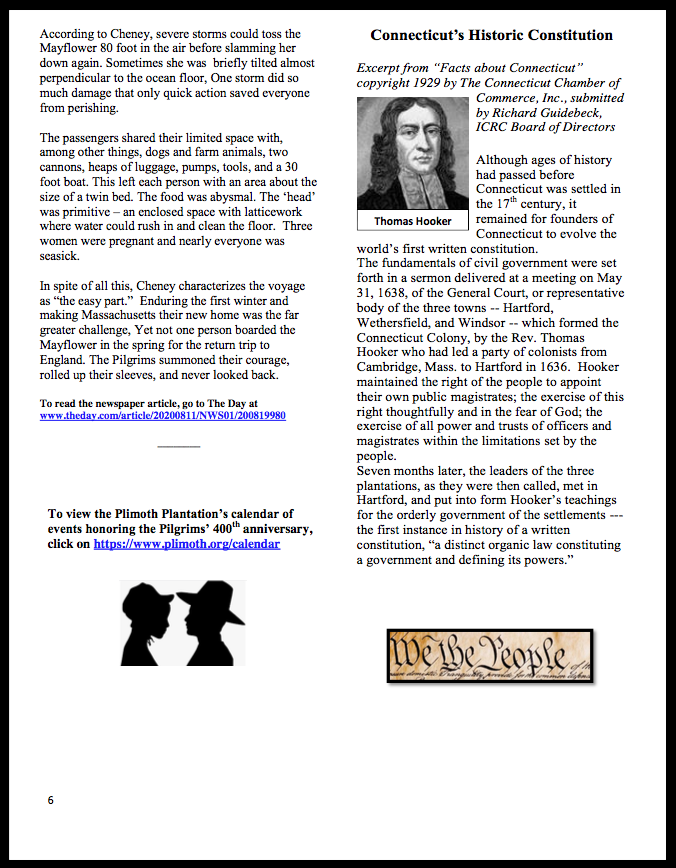

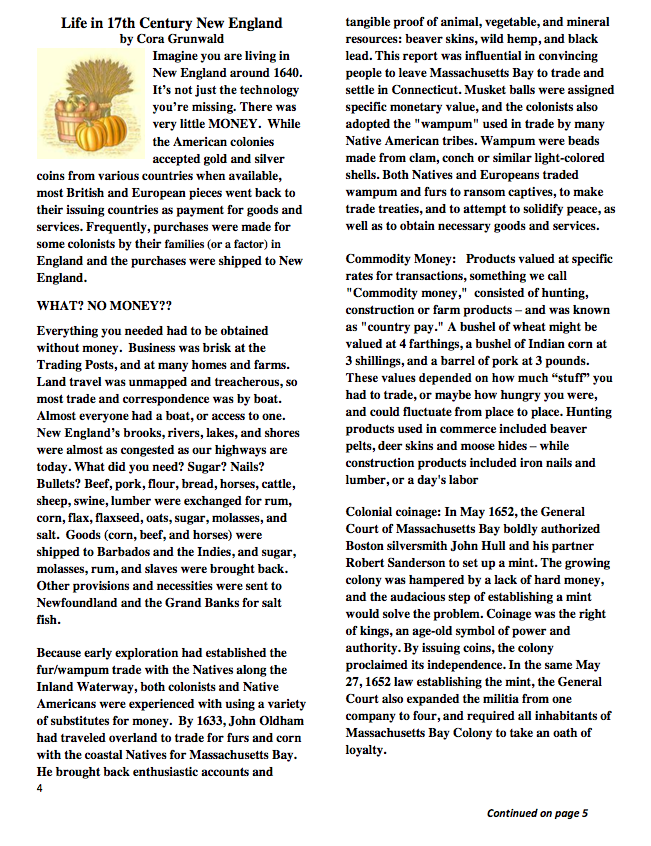

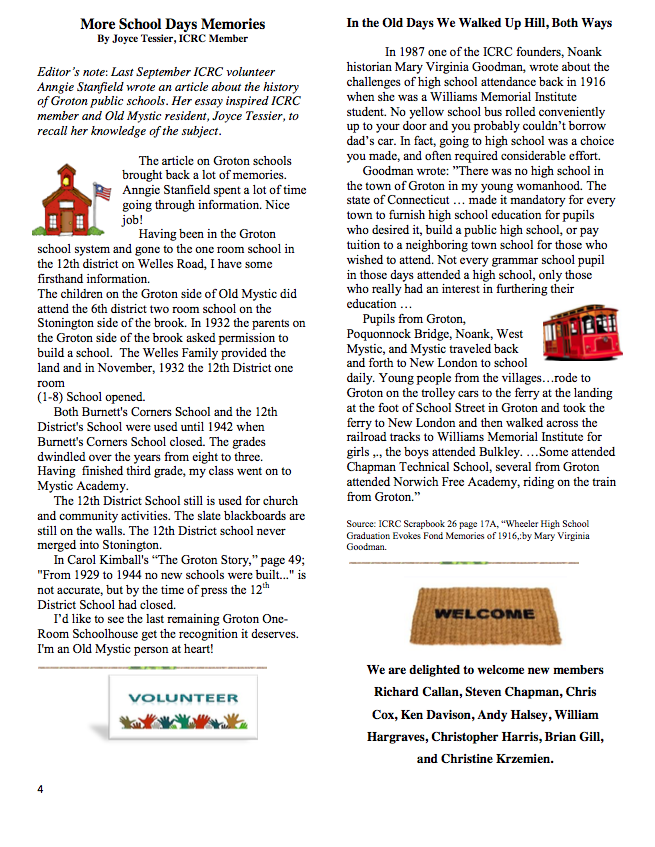

Mashantucket and Eastern Pequot representatives

honoring their ancestors at Fort Hill (1992)

When that memorial was finally installed, it came at an awkward time. In December of 1992, in the midst of a controversy over whether the John Mason statue in Mystic should be removed, Groton officials, a dozen Pequot tribal members, and some members of the public met on Fort Hill to place a simple boulder with a plaque reading, in part, “We raise this memorial to those gone before.” As Pequot representatives burned sweet grass, remembering the former village of Sassacus and Cassasinamon , Town officials hoped the message was politically neutral, suggesting that it honored 400 years of both Indian and Euro-American history.

Today, a passerby would never guess that a museum sat atop Fort Hill. The building’s footprint has been entirely erased. A half buried rock holds a bronze memorial, but if the light is shining in a certain way, the color of the rock camouflages the plaque. Several trees shade the spot where the trading post once opened its door to curious visitors. A nice green lawn has grown up to cover where boys and girls ran in and out of the Indian longhouse and wigwam. The sound of laughter and fun now are drowned out by the noise of the traffic on an otherwise quiet road.

Do you have a memory or a photograph of the Indian Memorial Museum that you would like to share with us? If so, we would be happy to hear your story and help preserve your photograph. Give us a call at 860-653-9771 or email us at ICRC06372@yahoo.com

|

|

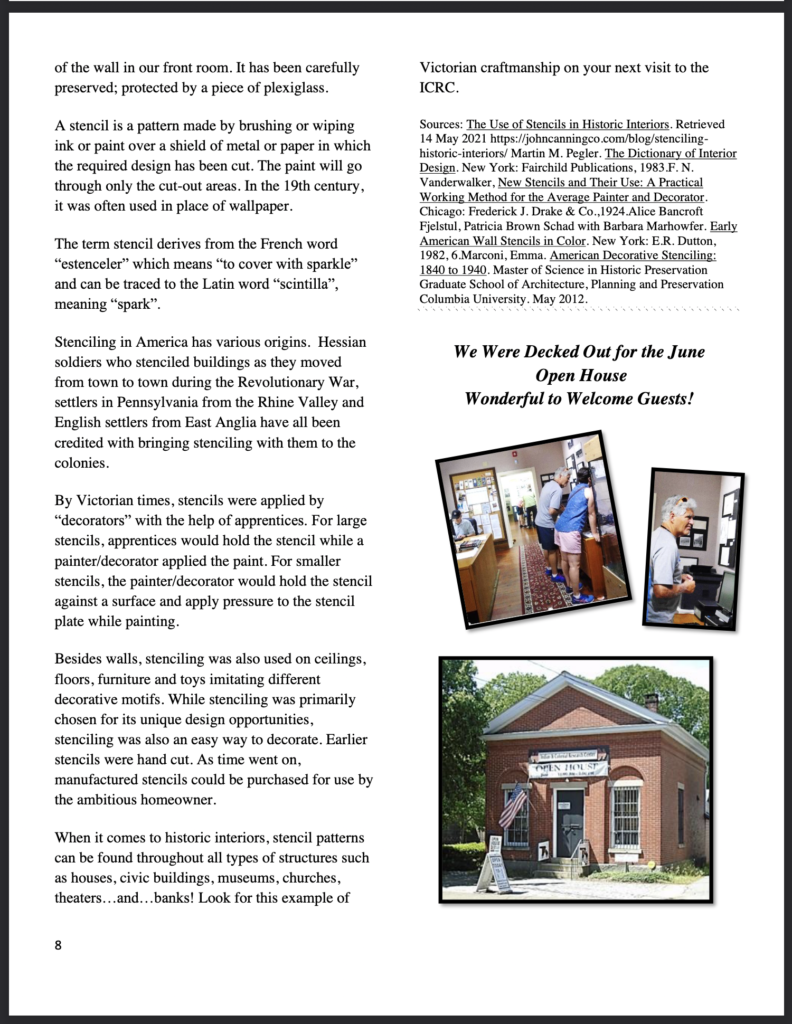

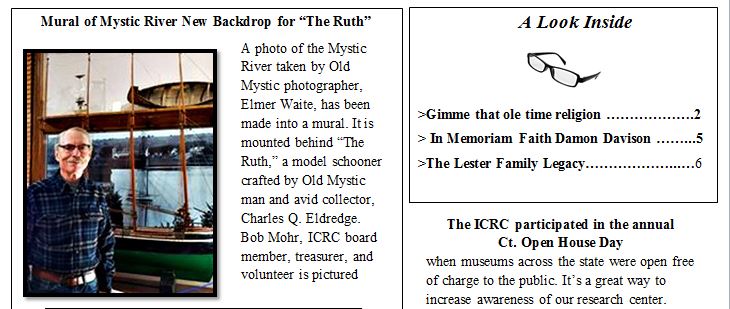

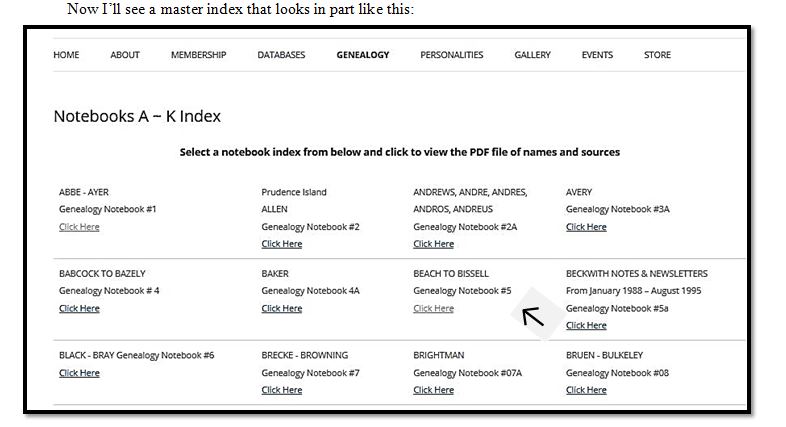

I C R C Hosts June Open House

The Indian and Colonial Research Center will proudly participate in this year’s Connecticut Open House Day on Saturday June 13, 2015. The ICRC will be open from 11:00 a.m. to 3:00 p.m. with volunteers and ICRC Board members greeting visitors. A special exhibit marking our 50th anniversary is on display in the front room and a special banner graces the front of the building! We hope YOU will be among the many guests who will stop by to view our unique collection!

|

|

Welcome New Members

Nice to have you aboard

I C R C extends a warm welcome to new members: John Haley II, Scott Miller and Roger Adams

|

|

Check This Out

The I C R C website is getting a fresh new look thanks to Marcus Mason Maronn – Great Job !

https://indianandcolonial.org

Also, we are on this locally based website as a Mystic attraction

http://thisismystic.com/to-do/museums/the-indian-colonial-research-center/

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sources:

Sources:

o well with recipes that have simple instructions like, “Face the stove.” I’m not up to anything complicated or exotic.

o well with recipes that have simple instructions like, “Face the stove.” I’m not up to anything complicated or exotic. much sugar as will sweeten it to your taste. Stir it over a fire until it is thick. Put it in a dish and make it into the form of a hedgehog. Slice more almonds long-ways to look like bristles. Put around it a pint of custard.”

much sugar as will sweeten it to your taste. Stir it over a fire until it is thick. Put it in a dish and make it into the form of a hedgehog. Slice more almonds long-ways to look like bristles. Put around it a pint of custard.”

page 5

page 5

Important Reminder: The I C R C relies on you, our members, for support. If you haven’t yet renewed your membership, please do so. If you have, many many thanks!

Important Reminder: The I C R C relies on you, our members, for support. If you haven’t yet renewed your membership, please do so. If you have, many many thanks!

Call the I C R C on Tuesdays or Thursdays between 10 & 4

Call the I C R C on Tuesdays or Thursdays between 10 & 4

A link to a

A link to a

Open House

Open House

For Volunteers

For Volunteers

By Carol Sommer, I C R C Volunteer

By Carol Sommer, I C R C Volunteer

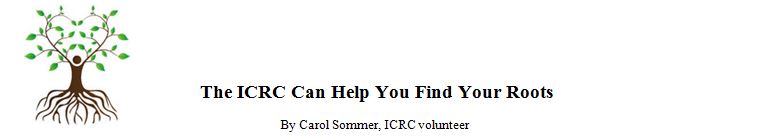

One of the more interesting aspects of serving on the Board of Directors at ICRC is the many opportunities that come to us that help educate us on the work being done here at ICRC.

One of the more interesting aspects of serving on the Board of Directors at ICRC is the many opportunities that come to us that help educate us on the work being done here at ICRC.

The Indian and Colonial Research Center will be a proud participant in the 12th annual Connecticut Open House Day on Saturday June 11, 2016. The one-day statewide event showcases the diversity of history, art, and tourism that our corner of New England offers. The ICRC will be open from 11:00 a.m. to 3:00 p.m. with volunteers and ICRC Board members greeting visitors. Mark your calendars! Stop by and help welcome guests or re-familiarize yourself will all the special resources our center has to offer!

The Indian and Colonial Research Center will be a proud participant in the 12th annual Connecticut Open House Day on Saturday June 11, 2016. The one-day statewide event showcases the diversity of history, art, and tourism that our corner of New England offers. The ICRC will be open from 11:00 a.m. to 3:00 p.m. with volunteers and ICRC Board members greeting visitors. Mark your calendars! Stop by and help welcome guests or re-familiarize yourself will all the special resources our center has to offer!

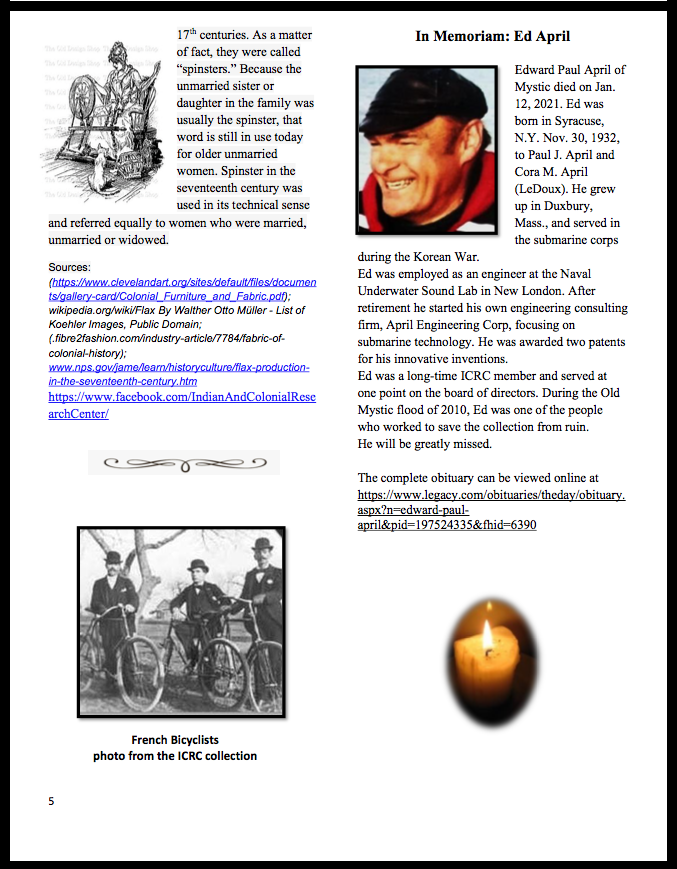

Indian Memorial House after storm damage in 1977

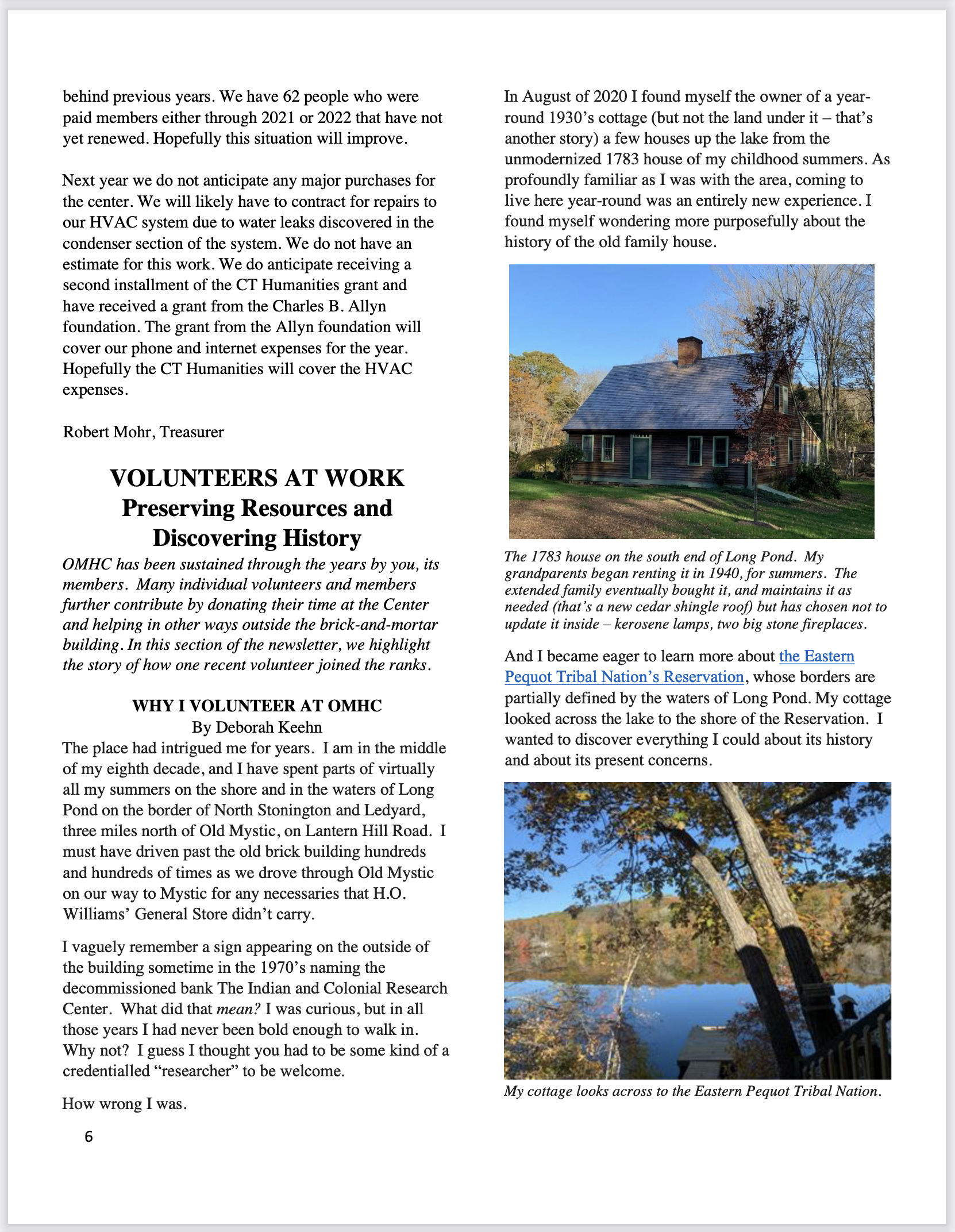

Indian Memorial House after storm damage in 1977